When Connecticut legalized recreational marijuana in 2021, the state’s lieutenant governor, Susan Bysiewicz, boasted that the new law was “crafted to repair the wounds left by the War on Drugs.” The move followed the same rationale that had motivated legalization in 18 other states: fewer resources exhausted on policing a drug that legalization advocates view as largely unharmful, fewer lives derailed by what they argue to be excessive lockups. In a sense, the plan worked: Possession arrests have fallen precipitously in the years since. But as Connecticut’s number of legal neighborhood weed shops has grown, so too has a problem that the state, like others that have eased marijuana laws, was seemingly ill-prepared to deal with: the rise of illegal marijuana shops.

Such shops are largely indistinguishable from state-sanctioned ones. They look the same and operate in the same neighborhoods, but they’ve never gone through the required licensing process to become a seller. (Beyond asking for paperwork, you’d be unlikely to know if you were shopping in an illegal store.) And they have become a headache for local law-enforcement agencies that want to crack down. “This is an epidemic within the state of Connecticut,” Ryan Evarts, a sergeant at the Norwalk Police Department, told me. The problem has become so pronounced that some states, including Connecticut, have recently passed laws giving law enforcement greater powers to police these shops.

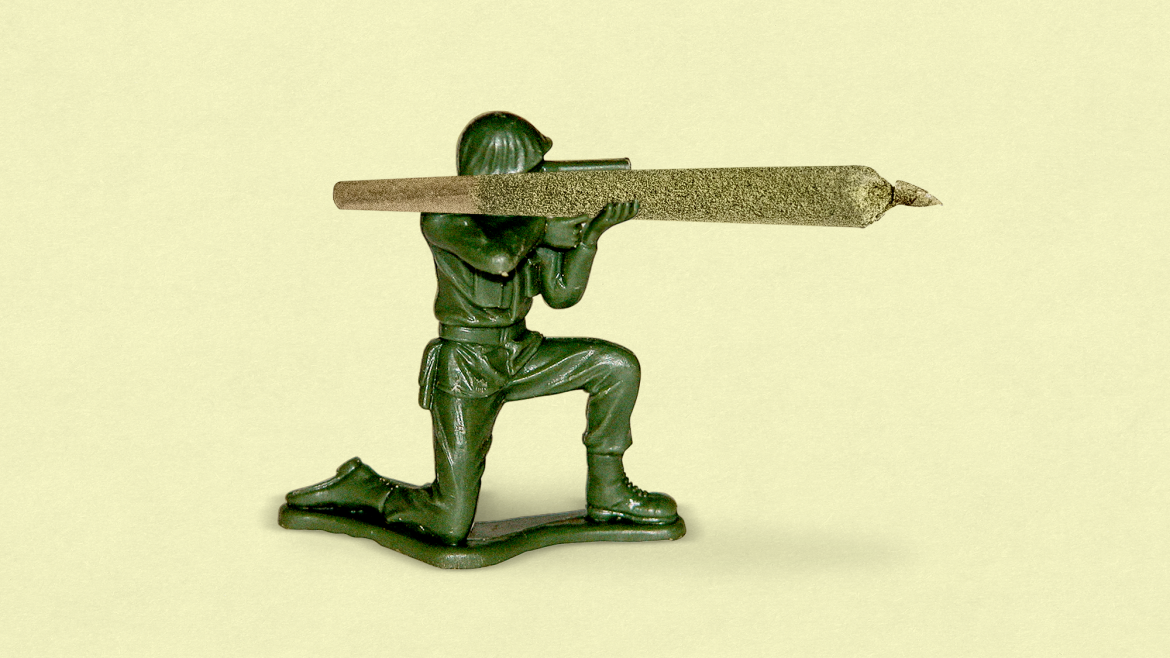

The result has been a strange new inversion: states with some of the loosest marijuana restrictions in the nation arresting and charging sellers of a drug that was made legal at least in part to move away from such charges. Since the beginning of last year, Connecticut has arrested dozens for selling pot out of illegal shops. From April to June 2025, California, supposedly a bastion of recreational cannabis, arrested 93 people for illegally selling, growing, and distributing weed, according to the state’s Department of Cannabis Control—the largest number of weed arrests in a three-month period since the state legalized the drug. Similar arrests have also been made within the past year in Illinois; Arizona; New Jersey; New York; Ohio; Washington, D.C.; and Washington State. It’s not just the owners of smoke shops who have been targeted—so have rank-and-file employees, according to news reports.

[Read: The GOP’s tipping point on weed]

There is a justifiable public-health rationale for going after these shops. In most states, legal weed must be independently tested for contaminants, such as lead and cadmium. Illegal products may not undergo such testing, in turn putting consumers at increased risk of long-term health complications, such as cancer. Some of these stores are also allowing cannabis to land in the hands of children, which is particularly concerning given research showing that cannabis can harm the developing brain. Multiple smoke shops in Connecticut that were raided had been caught selling products to minors.

Illegal sales of cannabis are bad for the states financially, too. Officials have invested time and money into setting up legal cannabis programs; by levying taxes on legal marijuana sales, states have turned recreational cannabis into a windfall. California expects to bring in more than $700 million in tax revenue from marijuana this year alone. States have a clear reason to crack down: Illegal weed sales might go untaxed. And if businesses can continue selling cannabis under the table, it dilutes the incentive for shops to go through the often long and arduous process of getting a cannabis-retailer license.

Police officers have also warned that some illegal cannabis shops are involved in and potentially funding other, more criminal enterprises. Police found guns and other drugs—including hallucinogenic mushrooms, fentanyl, and crack cocaine—during several recent arrests in Connecticut, according to press reports. In California, where the governor has created a task force on illegal cannabis, recent busts are part of a larger effort to disrupt criminal groups, including “Chinese organized crime,” Kevin McInerney, a commander at the Department of Cannabis Control, told me. McInerney did not cite any examples of operations explicitly tied to Chinese organized crime, but last year, ProPublica reported that America’s illegal cannabis market is dominated by “Chinese mobsters who roam from state to state, harvesting drugs and cash and overwhelming law enforcement with their resources and elusiveness.”

But not everyone is enthusiastic about using police to regulate the cannabis black market. “You can’t arrest your way out of problems like illicit markets,” Daniel Nagin, a criminology expert at Carnegie Mellon University, told me. “Targeted arrest strategies are effective only in a limited set of circumstances, like going after known high-rate offenders.”

Drug-policy advocates I spoke with emphasized that some operators of illegal weed shops may not have the resources to secure a coveted place in the legal market. A license to operate a cannabis shop in Connecticut can run up to $25,000, not including additional fees. Owners also must have measures in place to ensure that cannabis is not stolen or diverted, including programs to track each piece of cannabis that enters and leaves their store, as well as more traditional security systems, such as video-surveillance systems and a silent alarm.

If the problem is merely too few legal cannabis shops, the solution may seem simple, at least among those who argue that recreational marijuana should be legal: a loosening of the rules around cannabis licensing. “The solution isn’t to crack down harder, but to create more inclusive pathways into the legal market and to decriminalize cannabis at all levels,” Adrian Rocha, the director of policy for the Last Prisoner Project, a criminal-justice-reform group focused on drug policy, told me. For those who still break the law, other enforcement measures—such as fines—should solve the problem, Maritza Perez Medina, the director of federal affairs at the Drug Policy Alliance, told me.

But such arguments for how to deal with the problem of illegal weed fall flat. Los Angeles still has a problem with illegal dispensaries, even though the city has more than three times the number of legal dispensaries serving about the same population as Connecticut. And fines and other regulatory tools have time and again proved ineffective in stopping illegal behavior. Some shops in Connecticut, for example, have been busted more than once for selling illegal cannabis products. Even shutting down dispensaries doesn’t always fix these problems: When New York City closed an illegal smoke shop in the Bronx, it simply reopened next door.

Regardless of who is selling black-market weed and what their motivations are, if illegal sales continue to grow, they have the potential to put the legalization movement in jeopardy. Even in states that have already enacted law changes, one could imagine residents—and politicians—getting so sick of hearing about lawless cannabis shops, including those with guns and who are selling to kids, that they question the merits of legalization more generally. Throwing people in jail may not be ideal. But so far, no one has quite figured out a better plan.